_______________________________

Search: http://vtls.mcu.ac.th/

สืบค้นหนังสือห้องสมุด มจร. ทุกแห่งที่นี่

_______________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________

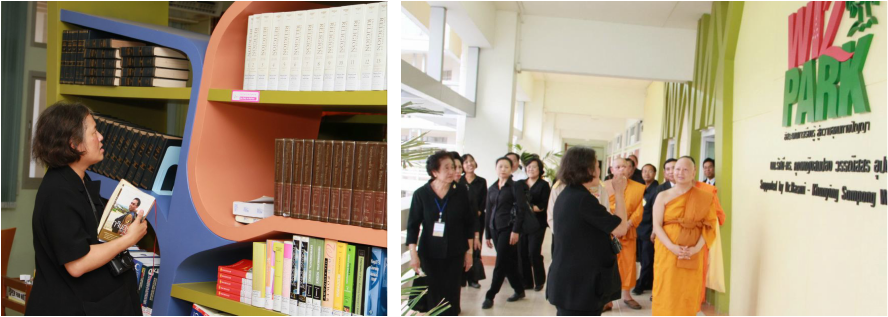

Wizpark is the learning center of Language Institute

____________________________________________________________________________________

Wizpark is the learning center of Language Institute

____________________________________________________________________________________

สมเด็จพระเทพรัตนราชสุดาฯ สยามบรมราชกุมารี เสด็จฯ เยี่ยมชมห้องสมุดสถาบันภาษา มจร.

ปฏิทินวันพระ ปี 2561

วันจันทร์ที่ 1 มกราคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนยี่(๒) ปีระกา) วันขึ้นปีใหม่

วันอังคารที่ 9 มกราคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนยี่(๒) ปีระกา)

วันอังคารที่ 16 มกราคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนยี่(๒) ปีระกา)

วันพุธที่ 24 มกราคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสาม(๓) ปีระกา)

วันพุธที่ 31 มกราคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสาม(๓) ปีระกา)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 8 กุมภาพันธ์ 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสาม(๓) ปีระกา)

วันพุธที่ 14 กุมภาพันธ์ 2561 (แรม ๑๔ ค่ำ เดือนสาม(๓) ปีระกา)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 22 กุมภาพันธ์ 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสี่(๔) ปีระกา)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 1 มีนาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสี่(๔) ปีระกา) วันมาฆบูชา

วันศุกร์ที่ 9 มีนาคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสี่(๔) ปีระกา)

วันศุกร์ที่ 16 มีนาคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสี่(๔) ปีระกา)

วันเสาร์ที่ 24 มีนาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนห้า(๕) ปีจอ)

วันเสาร์ที่ 31 มีนาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนห้า(๕) ปีจอ)

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 8 เมษายน 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนห้า(๕) ปีจอ)

วันเสาร์ที่ 14 เมษายน 2561 (แรม ๑๔ ค่ำ เดือนห้า(๕) ปีจอ) วันสงกรานต์

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 22 เมษายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนหก(๖) ปีจอ)

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 29 เมษายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนหก(๖) ปีจอ)

วันจันทร์ที่ 7 พฤษภาคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนหก(๖) ปีจอ)

วันจันทร์ที่ 14 พฤษภาคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนหก(๖) ปีจอ)

วันอังคารที่ 22 พฤษภาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนเจ็ด(๗) ปีจอ)

วันนอังคารที่ 29 พฤษภาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนเจ็ด(๗) ปีจอ) วันวิสาขบูชา

วันพุธที่ 6 มิถุนายน 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนเจ็ด(๗) ปีจอ) วันอัฏฐมีบูชา

วันอังคารที่ 12 มิถุนายน 2561 (แรม ๑๔ ค่ำ เดือนเจ็ด(๗) ปีจอ)

วันพุธที่ 20 มิถุนายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนแปด(๘) ปีจอ)

วันพุธที่ 27 มิถุนายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนแปด(๘) ปีจอ)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 5 กรกฎาคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนแปด(๘) ปีจอ)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 12 กรกฎาคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนแปด(๘) ปีจอ)

วันศุกร์ที่ 20 กรกฎาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนแปดหลัง(๘๘) ปีจอ)

วันศุกร์ที่ 27 กรกฎาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนแปดหลัง(๘๘) ปีจอ) วันอาสาฬหบูชา

วันเสาร์ที่ 28 กรกฎาคม 2561 (แรม ๑ ค่ำ เดือนแปดหลัง(๘๘) ปีจอ) วันเฉลิมฯ ร.10,วันเข้าพรรษา

วันเสาร์ที่ 4 สิงหาคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนแปดหลัง(๘๘) ปีจอ)

วันเสาร์ที่ 11 สิงหาคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนแปดหลัง(๘๘) ปีจอ)

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 19 สิงหาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนเก้า(๙) ปีจอ)

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 26 สิงหาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนเก้า(๙) ปีจอ)

วันจันทร์ที่ 3 กันยายน 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนเก้า(๙) ปีจอ)

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 9 กันยายน 2561 (แรม ๑๔ ค่ำ เดือนเก้า(๙) ปีจอ)

วันจันทร์ที่ 17 กันยายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสิบ(๑๐) ปีจอ)

วันจันทร์ที่ 24 กันยายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสิบ(๑๐) ปีจอ)

วันอังคารที่ 2 ตุลาคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสิบ(๑๐) ปีจอ)

วันอังคารที่ 9 ตุลาคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสิบ(๑๐) ปีจอ)

วันพุธที่ 17 ตุลาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสิบเอ็ด(๑๑) ปีจอ)

วันพุธที่ 24 ตุลาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสิบเอ็ด(๑๑) ปีจอ) วันออกพรรษา

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 1 พฤศจิกายน 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสิบเอ็ด(๑๑) ปีจอ)

วันพุธที่ 7 พฤศจิกายน 2561 (แรม ๑๔ ค่ำ เดือนสิบเอ็ด(๑๑) ปีจอ)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 15 พฤศจิกายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสิบสอง(๑๒) ปีจอ)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 22 พฤศจิกายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสิบสอง(๑๒) ปีจอ) วันลอยกระทง

วันศุกร์ที่ 30 พฤศจิกายน 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสิบสอง(๑๒) ปีจอ)

วันนศุกร์ที่ 7 ธันวาคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสิบสอง(๑๒) ปีจอ)

วันเสาร์ที่ 15 ธันวาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนอ้าย(๑) ปีจอ)

วันเสาร์ที่ 22 ธันวาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนอ้าย(๑) ปีจอ)

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 30 ธันวาคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนอ้าย(๑) ปีจอ)

วันจันทร์ที่ 1 มกราคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนยี่(๒) ปีระกา) วันขึ้นปีใหม่

วันอังคารที่ 9 มกราคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนยี่(๒) ปีระกา)

วันอังคารที่ 16 มกราคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนยี่(๒) ปีระกา)

วันพุธที่ 24 มกราคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสาม(๓) ปีระกา)

วันพุธที่ 31 มกราคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสาม(๓) ปีระกา)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 8 กุมภาพันธ์ 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสาม(๓) ปีระกา)

วันพุธที่ 14 กุมภาพันธ์ 2561 (แรม ๑๔ ค่ำ เดือนสาม(๓) ปีระกา)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 22 กุมภาพันธ์ 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสี่(๔) ปีระกา)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 1 มีนาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสี่(๔) ปีระกา) วันมาฆบูชา

วันศุกร์ที่ 9 มีนาคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสี่(๔) ปีระกา)

วันศุกร์ที่ 16 มีนาคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสี่(๔) ปีระกา)

วันเสาร์ที่ 24 มีนาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนห้า(๕) ปีจอ)

วันเสาร์ที่ 31 มีนาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนห้า(๕) ปีจอ)

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 8 เมษายน 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนห้า(๕) ปีจอ)

วันเสาร์ที่ 14 เมษายน 2561 (แรม ๑๔ ค่ำ เดือนห้า(๕) ปีจอ) วันสงกรานต์

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 22 เมษายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนหก(๖) ปีจอ)

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 29 เมษายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนหก(๖) ปีจอ)

วันจันทร์ที่ 7 พฤษภาคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนหก(๖) ปีจอ)

วันจันทร์ที่ 14 พฤษภาคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนหก(๖) ปีจอ)

วันอังคารที่ 22 พฤษภาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนเจ็ด(๗) ปีจอ)

วันนอังคารที่ 29 พฤษภาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนเจ็ด(๗) ปีจอ) วันวิสาขบูชา

วันพุธที่ 6 มิถุนายน 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนเจ็ด(๗) ปีจอ) วันอัฏฐมีบูชา

วันอังคารที่ 12 มิถุนายน 2561 (แรม ๑๔ ค่ำ เดือนเจ็ด(๗) ปีจอ)

วันพุธที่ 20 มิถุนายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนแปด(๘) ปีจอ)

วันพุธที่ 27 มิถุนายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนแปด(๘) ปีจอ)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 5 กรกฎาคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนแปด(๘) ปีจอ)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 12 กรกฎาคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนแปด(๘) ปีจอ)

วันศุกร์ที่ 20 กรกฎาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนแปดหลัง(๘๘) ปีจอ)

วันศุกร์ที่ 27 กรกฎาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนแปดหลัง(๘๘) ปีจอ) วันอาสาฬหบูชา

วันเสาร์ที่ 28 กรกฎาคม 2561 (แรม ๑ ค่ำ เดือนแปดหลัง(๘๘) ปีจอ) วันเฉลิมฯ ร.10,วันเข้าพรรษา

วันเสาร์ที่ 4 สิงหาคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนแปดหลัง(๘๘) ปีจอ)

วันเสาร์ที่ 11 สิงหาคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนแปดหลัง(๘๘) ปีจอ)

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 19 สิงหาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนเก้า(๙) ปีจอ)

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 26 สิงหาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนเก้า(๙) ปีจอ)

วันจันทร์ที่ 3 กันยายน 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนเก้า(๙) ปีจอ)

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 9 กันยายน 2561 (แรม ๑๔ ค่ำ เดือนเก้า(๙) ปีจอ)

วันจันทร์ที่ 17 กันยายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสิบ(๑๐) ปีจอ)

วันจันทร์ที่ 24 กันยายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสิบ(๑๐) ปีจอ)

วันอังคารที่ 2 ตุลาคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสิบ(๑๐) ปีจอ)

วันอังคารที่ 9 ตุลาคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสิบ(๑๐) ปีจอ)

วันพุธที่ 17 ตุลาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสิบเอ็ด(๑๑) ปีจอ)

วันพุธที่ 24 ตุลาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสิบเอ็ด(๑๑) ปีจอ) วันออกพรรษา

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 1 พฤศจิกายน 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสิบเอ็ด(๑๑) ปีจอ)

วันพุธที่ 7 พฤศจิกายน 2561 (แรม ๑๔ ค่ำ เดือนสิบเอ็ด(๑๑) ปีจอ)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 15 พฤศจิกายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสิบสอง(๑๒) ปีจอ)

วันพฤหัสบดีที่ 22 พฤศจิกายน 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสิบสอง(๑๒) ปีจอ) วันลอยกระทง

วันศุกร์ที่ 30 พฤศจิกายน 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนสิบสอง(๑๒) ปีจอ)

วันนศุกร์ที่ 7 ธันวาคม 2561 (แรม ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนสิบสอง(๑๒) ปีจอ)

วันเสาร์ที่ 15 ธันวาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๘ ค่ำ เดือนอ้าย(๑) ปีจอ)

วันเสาร์ที่ 22 ธันวาคม 2561 (ขึ้น ๑๕ ค่ำ เดือนอ้าย(๑) ปีจอ)

วันอาทิตย์ที่ 30 ธันวาคม 2561 (แรม ๘ ค่ำ เดือนอ้าย(๑) ปีจอ)

โลกุตระกับโลกิยะ มีเส้นแบ่งบางๆ ยากที่จะแบ่ง

วันนี้ผู้เขียนได้สนทนาธรรมกับกัลยาณมิตร ซึ่งท่านเป็นผู้มีความรู้ทางธรรมขั้นปรมาจารย์ ผมจำชื่อท่านไม่ได้แล้ว

ครับ ซึ่งเป็นข้อบกพร่องที่ไม่น่าให้อภัย โดยผมได้ทักทายท่านก่อนว่า

"ท่านครับท่านเคยอยู่หนังสือพิมพ์(ฉบับหนึ่ง)ใช่ไหมครับ"

ท่านตอบว่า "ใช่ครับ"

จากการถามไถ่ได้ทราบว่าท่านได้เปรียญธรรม ๗ ประโยค ส่วนผู้เขียนมีความรู้น้อยแค่นักธรรมเอก

การสนทนาจึงดำเนินไปด้วยลักษณะขอความรู้จากผู้รู้ ซึ่งได้รับประโยชน์อย่างมากมาย แต่มีคำคำหนึ่งที่ท่านพูดแล้วทำให้ผม

อยากค้นคว้าหาความรู้เพิ่มเติม และเป็นที่มาของการเขียนบทความ "โลกุตระกับโลกิยะ มันมีเส้นแบ่งบางๆ ยากที่จะแบ่ง"

โลกิย (โล-กิ-ยะ) แปลว่า วิสัยของโลก, สภาวะเนื่องในโลก,ยังเกี่ยวข้องกับโลก, เรื่องทางโลก, ธรรมดาโลก, ใช้ว่า

โลกีย์ หรือ โลกิยะ ก็มี โลกิยะ หมายถึงภาวะความเป็นไปที่ยังวนเวียนอยู่ในภพสาม คือ กามภพ รูปภพ อรูปภพ คือยังเกี่ยวข้องอยู่กับ เรื่องกาม ตัณหา ทิฏฐิ อวิชชาโลกิยะ ที่ใช้ในรูปของโลกีย์ ในทางโลกมักใช้หมายถึงเรื่องเกี่ยวกับกามารมณ์ คือ

รูป เสียง กลิ่น รส สัมผัส เช่นใช้ว่า กามโลกีย์ คาวโลกีย์

เหตุแห่งโลกียะ คือ ความไม่รู้ (อวิชชา)

ผลแห่งโลกียะ คือ สมมุติบัญญัติ (เปลือก)

เมื่อมีความไม่รู้เป็นเหตุต้น มนุษย์จึงสมมุติสิ่งต่างๆ บัญญัติสิ่งต่างๆ ขึ้นมาเรียก เป็นผล ขึ้นมาจดจำ ขึ้นมาปรุง

แต่งว่าแบบนั้นดี แบบนี้ชั่ว แล้วยึดมั่นถือมั่นจดจำไว้ ดังนั้น ความไม่รู้เป็นเหตุ สมมุติจึงเป็นผล เรื่องของโลกีย์ จึงมีแต่เรื่องสมมุติ มายา ละครชีวิต ดั่งคำว่าโลกนี้คือละคร

บทบาทบางตอนยอกย้อนยับเยินหมุนเวียนเปลี่ยนไป ไม่มีอะไรจีรังยั่งยืนในความเป็นสมมุติมายาแห่งโลก ดังนั้น บุคคลผู้หลงโลก จึงหลงเพียงมายา หลงเพียงความ

สมมุติ ความเป็นจริงของชีวิต นั้นอยู่ที่ชีวิตจริงๆ ในปัจจุบัน แต่ละขณะ ทำอะไร ควรค่าแก่ความเป็นมนุษย์หรือไม่ หากไม่มีอวิชชา (ความไม่รู้) ก็ไม่มีการสมมุติบัญญัติ

หากไม่มีการยึดถือสมมุติบัญญัติ ก็ไม่มีอวิชชา ทั้งสองขาดกันไม่ได้ ขาดด้านใดด้านหนึ่งมักมีปัญหา

โลกุตร (โล-กุด-ตะ-ระ) แปลว่า พ้นโลก อยู่เหนือวิสัยของโลก มิใช่วิสัยของโลก โลกุตระ หมายถึงภาวะที่หลุดพ้นแล้วจากโลกิยะ ไม่เกี่ยวข้องกับกาม ตัณหา ทิฏฐิ

อวิชชาอีกต่อไป ได้แก่ธรรม ๙ ประการซึ่งเรียกว่า นวโลกุตรธรรม หรือ โลกุตรธรรม ๙ (มรรค ๔+ผล ๔+นิพพาน ๑) เหตุแห่งโลกุตระ คือ ว่างจากสมมุติ (กิเลสนิพพาน)

ผลแห่งโลกุตระ คือ บรรลุสัจธรรม (แก่น) เมื่อหมดไปแห่งสมมุติบัญญัติ เสมือนบุคคลปลอกเปลือกสิ่งใดสิ่งหนึ่งออกหมด ย่อมเห็นถึงแก่นแท้ ฉันใดก็ฉันนั้น เมื่อหมดสิ้น

กิเลส ความยึดถือในสมมุติ ในบัญญัติใดๆ ทั้งมวล ย่อมเห็นสัจธรรมที่เที่ยงแท้บริสุทธิ์ไม่ปรุงแต่ง เพราะว่าการสมมุติบัญญัตินี้เองที่ปิดบังความจริง เมื่อสิ้นไปเสีย ความจริง

ก็ปรากฏ เพราะสัจธรรมคือความเป็นจริงที่มีมาอยู่ก่อนแล้ว ไม่มีที่สิ้นสุด เมื่อสัจธรรมบังเกิดขึ้น ทำให้บุคคลเข้าใจถึงสมมุติมายาแห่งโลก ความหลง ความยึดถือสมมุติ

ก็พลันสูญไป เพราะความรู้แจ้งเห็นจริงในสัจธรรมอันบริสุทธิ์ เพราะความว่างจากสมมุติ จึงเห็นสัจธรรมโลกียะและโลกุตระมีวัฎฏะของมันอย่างไม่มีที่สุดเพียงวงจรของโลกียะ

อาจแบ่งเป็นช่วงสั้นๆ การหมุนเพราะความไม่รู้เป็นเหตุ คือ ความบริสุทธิ์ของจิตเดิมแท้ของมนุษย์ ที่มนุษย์เกิดมาเป็นผู้ไม่รู้มาแต่ก่อน แม้จิตจะบริสุทธิ์ก็ตาม

โลกียะเป็นผล คือ ความหลงยึดถือในสมมุติมายาแห่งโลก ทำให้ไม่อาจพ้นโลกียะไปได้ ไม่อาจเห็นสัจธรรมตามจริงได้ วัฎฏะด้านสมมุติบัญญัติ ที่เกิดโดยอุปโลกกันขึ้นมา

มีหลายระดับ รวมถึงหน้าที่การงานความเป็นอยู่ของสังคม ที่กำลังดำเนินไปอยู่ในโลก เพื่อให้โลกเกิดความสันติสุขชั่ววงจรชีวิตหนึ่งๆ ของสิ่งมีชีวิตสมมติขึ้นโดยเฉพาะมนุษย์

ชั่งสรรค์ปั้นแต่งขึ้นมาหลากหลายเท่าปัญญามี(ปัญญาอันเกิดมาจากอวิชชา) วัฎฏะของสมมุติ นำมาซึ่ง “ทุกข์” ทำให้บุคคลแสวงหาทางหลุดพ้นจากทุกข์ สัจธรรมความจริงอันพ้นจากสมมุตินำมาซึ่ง “ความพ้นทุกข์” วัฎฏะของสัจธรรม คือ สัจธรรมความจริงอันมีอยู่ก่อนแล้ว ได้ปรากฏให้ผู้คนได้เห็นได้เข้าใจ เช่น การตายอันเนื่องมาจากการเกิด มีให้เห็นทุกวัน เป็นเครื่องเตือนทุกคนว่าความตายเป็นของแน่แท้ ชีวิตเป็นของไม่เที่ยง เพราะสัจธรรมความจริง มีอยู่แล้วโดยธรรมชาติ ไม่ต้องแสวงหาหรือสร้างใหม่

แต่ความเข้าใจในสมมุติ ก็มีประโยชน์ช่วยประคับประคอง ให้บุคคลที่เกิดมาทีหลังที่ยังไม่รู้ประสีประสาอะไรให้สำเนียก ได้เข้าใจ ยึดถือเป็นเบื้องต้นก่อน จนกว่าจะพบสัจจธรรมด้วยตนเอง

อย่างไรก็ตามความหนุนเนื่องแห่งทางโลกกับทางธรรม ยังต้องควบคู่กันไป “ทางโลกก็ดำเนินไป” “ทางธรรมก็ต้องดำเนินไป” เช่นกัน เส้นแบ่งทั้งทางธรรมและทางโลกมันบอบบางมาก ถ้าทางโลกเหวี่ยงแรงไปเพราะเหตุแห่งการให้น้ำหนักมากกว่า จะทำให้ทางธรรมขาดสะบั้นกระเด็นออกไปแบบไร้ทิศทาง เมื่อโลกหมุนไประบบเศรษฐกิจก็ต้องมีโลกีย์วิสัยยังต้องแฝงอยู่ เพียงแต่ผุ้เผยแผ่ธรรมอย่านำความรักโลภโกรธหลง มาฝังไว้ในธรรมคำสอน มันอาจเป็นระเบิดลูกมหึมา ในการทำลายล้างมวลมนุษยชาติด้วยกัน เกิดการแก่งแย่งแบบไร้คุณธรรม แต่ขณะเดียวกันก็อย่าให้แรงเหวี่ยงของโลกทำให้หลุดออกจากทางโลก มากจนเกินไปเกินกว่าที่จะสมานกันได้ ดังนั้น ทางโลกและทางธรรม จึงต้องหมุนไปพร้อมๆ กันให้เกิดความสมดุลย์ ต่างต้องพึ่งพาอาศัยกันเกิดขึ้นแล้วดับไป ตามกาล แต่ละยุค แต่ละสมัยหมุนเวียนเปลี่ยนไป อย่างมีนัยสำคัญที่ไม่ควรแยก เพียงแตกต่างที่กาลเวลาที่ดำเนินไปไม่มีสิ้นสุด โดยอาศัยความไม่รู้อยู่ก่อน อันเป็นความจริงของมนุษย์ และอาศัยการสมมุติบัญญัติสิ่งต่างๆ เพื่อให้โลกสงบสุข เช่น กฏระเบียบของการอยู่ร่วมสังคม เป็นกลไกลของโลก ส่วน(สัจจะ)ธรรมนั้น ต้องอาศัยกลไกลธรรม(ชาติ)แสดงตัว บีบคั้นให้มนุษย์ประสบด้วยตัวเอง เพราะมันมีอยู่แล้ว มีอยู่จริง มีพลังพอที่จะทำให้มนุษย์ได้คิด ได้ประจักษ์แจ้งในพลังแห่งธรรมชาตินั้น เป็นธรรม(ชาติ)ที่ยังคงดำรงอยู่และหมุนไปเช่นกันกับสมมุติบัญญัติที่มนุษย์สร้างอันส่งผลร้ายต่อมวลมนุษย์ ซึ่งมันได้แสดงถึงพิษสงอันเป็น ความทุกข์ เป็นสัจธรรมของมันอย่างแท้จริง ทำให้เหล่ามนุษย์ ต้องประจักษ์แจ้งในความจริง ว่า ""โลกียะ" กับ "โลกุตระ" ต้องหมุนไปด้วยกันโดยมีเส้นแบ่งบางๆ ที่แยกออกจากกันแทบไม่ได้

ประสบ สุระพินิจ

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ครับ ซึ่งเป็นข้อบกพร่องที่ไม่น่าให้อภัย โดยผมได้ทักทายท่านก่อนว่า

"ท่านครับท่านเคยอยู่หนังสือพิมพ์(ฉบับหนึ่ง)ใช่ไหมครับ"

ท่านตอบว่า "ใช่ครับ"

จากการถามไถ่ได้ทราบว่าท่านได้เปรียญธรรม ๗ ประโยค ส่วนผู้เขียนมีความรู้น้อยแค่นักธรรมเอก

การสนทนาจึงดำเนินไปด้วยลักษณะขอความรู้จากผู้รู้ ซึ่งได้รับประโยชน์อย่างมากมาย แต่มีคำคำหนึ่งที่ท่านพูดแล้วทำให้ผม

อยากค้นคว้าหาความรู้เพิ่มเติม และเป็นที่มาของการเขียนบทความ "โลกุตระกับโลกิยะ มันมีเส้นแบ่งบางๆ ยากที่จะแบ่ง"

โลกิย (โล-กิ-ยะ) แปลว่า วิสัยของโลก, สภาวะเนื่องในโลก,ยังเกี่ยวข้องกับโลก, เรื่องทางโลก, ธรรมดาโลก, ใช้ว่า

โลกีย์ หรือ โลกิยะ ก็มี โลกิยะ หมายถึงภาวะความเป็นไปที่ยังวนเวียนอยู่ในภพสาม คือ กามภพ รูปภพ อรูปภพ คือยังเกี่ยวข้องอยู่กับ เรื่องกาม ตัณหา ทิฏฐิ อวิชชาโลกิยะ ที่ใช้ในรูปของโลกีย์ ในทางโลกมักใช้หมายถึงเรื่องเกี่ยวกับกามารมณ์ คือ

รูป เสียง กลิ่น รส สัมผัส เช่นใช้ว่า กามโลกีย์ คาวโลกีย์

เหตุแห่งโลกียะ คือ ความไม่รู้ (อวิชชา)

ผลแห่งโลกียะ คือ สมมุติบัญญัติ (เปลือก)

เมื่อมีความไม่รู้เป็นเหตุต้น มนุษย์จึงสมมุติสิ่งต่างๆ บัญญัติสิ่งต่างๆ ขึ้นมาเรียก เป็นผล ขึ้นมาจดจำ ขึ้นมาปรุง

แต่งว่าแบบนั้นดี แบบนี้ชั่ว แล้วยึดมั่นถือมั่นจดจำไว้ ดังนั้น ความไม่รู้เป็นเหตุ สมมุติจึงเป็นผล เรื่องของโลกีย์ จึงมีแต่เรื่องสมมุติ มายา ละครชีวิต ดั่งคำว่าโลกนี้คือละคร

บทบาทบางตอนยอกย้อนยับเยินหมุนเวียนเปลี่ยนไป ไม่มีอะไรจีรังยั่งยืนในความเป็นสมมุติมายาแห่งโลก ดังนั้น บุคคลผู้หลงโลก จึงหลงเพียงมายา หลงเพียงความ

สมมุติ ความเป็นจริงของชีวิต นั้นอยู่ที่ชีวิตจริงๆ ในปัจจุบัน แต่ละขณะ ทำอะไร ควรค่าแก่ความเป็นมนุษย์หรือไม่ หากไม่มีอวิชชา (ความไม่รู้) ก็ไม่มีการสมมุติบัญญัติ

หากไม่มีการยึดถือสมมุติบัญญัติ ก็ไม่มีอวิชชา ทั้งสองขาดกันไม่ได้ ขาดด้านใดด้านหนึ่งมักมีปัญหา

โลกุตร (โล-กุด-ตะ-ระ) แปลว่า พ้นโลก อยู่เหนือวิสัยของโลก มิใช่วิสัยของโลก โลกุตระ หมายถึงภาวะที่หลุดพ้นแล้วจากโลกิยะ ไม่เกี่ยวข้องกับกาม ตัณหา ทิฏฐิ

อวิชชาอีกต่อไป ได้แก่ธรรม ๙ ประการซึ่งเรียกว่า นวโลกุตรธรรม หรือ โลกุตรธรรม ๙ (มรรค ๔+ผล ๔+นิพพาน ๑) เหตุแห่งโลกุตระ คือ ว่างจากสมมุติ (กิเลสนิพพาน)

ผลแห่งโลกุตระ คือ บรรลุสัจธรรม (แก่น) เมื่อหมดไปแห่งสมมุติบัญญัติ เสมือนบุคคลปลอกเปลือกสิ่งใดสิ่งหนึ่งออกหมด ย่อมเห็นถึงแก่นแท้ ฉันใดก็ฉันนั้น เมื่อหมดสิ้น

กิเลส ความยึดถือในสมมุติ ในบัญญัติใดๆ ทั้งมวล ย่อมเห็นสัจธรรมที่เที่ยงแท้บริสุทธิ์ไม่ปรุงแต่ง เพราะว่าการสมมุติบัญญัตินี้เองที่ปิดบังความจริง เมื่อสิ้นไปเสีย ความจริง

ก็ปรากฏ เพราะสัจธรรมคือความเป็นจริงที่มีมาอยู่ก่อนแล้ว ไม่มีที่สิ้นสุด เมื่อสัจธรรมบังเกิดขึ้น ทำให้บุคคลเข้าใจถึงสมมุติมายาแห่งโลก ความหลง ความยึดถือสมมุติ

ก็พลันสูญไป เพราะความรู้แจ้งเห็นจริงในสัจธรรมอันบริสุทธิ์ เพราะความว่างจากสมมุติ จึงเห็นสัจธรรมโลกียะและโลกุตระมีวัฎฏะของมันอย่างไม่มีที่สุดเพียงวงจรของโลกียะ

อาจแบ่งเป็นช่วงสั้นๆ การหมุนเพราะความไม่รู้เป็นเหตุ คือ ความบริสุทธิ์ของจิตเดิมแท้ของมนุษย์ ที่มนุษย์เกิดมาเป็นผู้ไม่รู้มาแต่ก่อน แม้จิตจะบริสุทธิ์ก็ตาม

โลกียะเป็นผล คือ ความหลงยึดถือในสมมุติมายาแห่งโลก ทำให้ไม่อาจพ้นโลกียะไปได้ ไม่อาจเห็นสัจธรรมตามจริงได้ วัฎฏะด้านสมมุติบัญญัติ ที่เกิดโดยอุปโลกกันขึ้นมา

มีหลายระดับ รวมถึงหน้าที่การงานความเป็นอยู่ของสังคม ที่กำลังดำเนินไปอยู่ในโลก เพื่อให้โลกเกิดความสันติสุขชั่ววงจรชีวิตหนึ่งๆ ของสิ่งมีชีวิตสมมติขึ้นโดยเฉพาะมนุษย์

ชั่งสรรค์ปั้นแต่งขึ้นมาหลากหลายเท่าปัญญามี(ปัญญาอันเกิดมาจากอวิชชา) วัฎฏะของสมมุติ นำมาซึ่ง “ทุกข์” ทำให้บุคคลแสวงหาทางหลุดพ้นจากทุกข์ สัจธรรมความจริงอันพ้นจากสมมุตินำมาซึ่ง “ความพ้นทุกข์” วัฎฏะของสัจธรรม คือ สัจธรรมความจริงอันมีอยู่ก่อนแล้ว ได้ปรากฏให้ผู้คนได้เห็นได้เข้าใจ เช่น การตายอันเนื่องมาจากการเกิด มีให้เห็นทุกวัน เป็นเครื่องเตือนทุกคนว่าความตายเป็นของแน่แท้ ชีวิตเป็นของไม่เที่ยง เพราะสัจธรรมความจริง มีอยู่แล้วโดยธรรมชาติ ไม่ต้องแสวงหาหรือสร้างใหม่

แต่ความเข้าใจในสมมุติ ก็มีประโยชน์ช่วยประคับประคอง ให้บุคคลที่เกิดมาทีหลังที่ยังไม่รู้ประสีประสาอะไรให้สำเนียก ได้เข้าใจ ยึดถือเป็นเบื้องต้นก่อน จนกว่าจะพบสัจจธรรมด้วยตนเอง

อย่างไรก็ตามความหนุนเนื่องแห่งทางโลกกับทางธรรม ยังต้องควบคู่กันไป “ทางโลกก็ดำเนินไป” “ทางธรรมก็ต้องดำเนินไป” เช่นกัน เส้นแบ่งทั้งทางธรรมและทางโลกมันบอบบางมาก ถ้าทางโลกเหวี่ยงแรงไปเพราะเหตุแห่งการให้น้ำหนักมากกว่า จะทำให้ทางธรรมขาดสะบั้นกระเด็นออกไปแบบไร้ทิศทาง เมื่อโลกหมุนไประบบเศรษฐกิจก็ต้องมีโลกีย์วิสัยยังต้องแฝงอยู่ เพียงแต่ผุ้เผยแผ่ธรรมอย่านำความรักโลภโกรธหลง มาฝังไว้ในธรรมคำสอน มันอาจเป็นระเบิดลูกมหึมา ในการทำลายล้างมวลมนุษยชาติด้วยกัน เกิดการแก่งแย่งแบบไร้คุณธรรม แต่ขณะเดียวกันก็อย่าให้แรงเหวี่ยงของโลกทำให้หลุดออกจากทางโลก มากจนเกินไปเกินกว่าที่จะสมานกันได้ ดังนั้น ทางโลกและทางธรรม จึงต้องหมุนไปพร้อมๆ กันให้เกิดความสมดุลย์ ต่างต้องพึ่งพาอาศัยกันเกิดขึ้นแล้วดับไป ตามกาล แต่ละยุค แต่ละสมัยหมุนเวียนเปลี่ยนไป อย่างมีนัยสำคัญที่ไม่ควรแยก เพียงแตกต่างที่กาลเวลาที่ดำเนินไปไม่มีสิ้นสุด โดยอาศัยความไม่รู้อยู่ก่อน อันเป็นความจริงของมนุษย์ และอาศัยการสมมุติบัญญัติสิ่งต่างๆ เพื่อให้โลกสงบสุข เช่น กฏระเบียบของการอยู่ร่วมสังคม เป็นกลไกลของโลก ส่วน(สัจจะ)ธรรมนั้น ต้องอาศัยกลไกลธรรม(ชาติ)แสดงตัว บีบคั้นให้มนุษย์ประสบด้วยตัวเอง เพราะมันมีอยู่แล้ว มีอยู่จริง มีพลังพอที่จะทำให้มนุษย์ได้คิด ได้ประจักษ์แจ้งในพลังแห่งธรรมชาตินั้น เป็นธรรม(ชาติ)ที่ยังคงดำรงอยู่และหมุนไปเช่นกันกับสมมุติบัญญัติที่มนุษย์สร้างอันส่งผลร้ายต่อมวลมนุษย์ ซึ่งมันได้แสดงถึงพิษสงอันเป็น ความทุกข์ เป็นสัจธรรมของมันอย่างแท้จริง ทำให้เหล่ามนุษย์ ต้องประจักษ์แจ้งในความจริง ว่า ""โลกียะ" กับ "โลกุตระ" ต้องหมุนไปด้วยกันโดยมีเส้นแบ่งบางๆ ที่แยกออกจากกันแทบไม่ได้

ประสบ สุระพินิจ

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

TODAY in the Past

Kamsing Srinok (คำสิงห์ ศรีนอก), who is also known under the pen name of

Lao Kam Hom (ลาวคำหอม), is a low-profiled but powerful writer, whose short stories

recreate northeastern village life. He was born on 25 December 1930, in

Nakhorn Rachasima Province in Northeastern of Thailand. His most acclaimed

short story, Fa Bo Kan (ฟ้าบ่กั้น) is about the hardship the Northeasterners

must face during a cruel drought.

-1952 he worked as Forestry office in Chiang Mai Province.

-1958 he return to farmer in Nakorn Rachasima. ( PM. Sarit Thanarat)cruel

-1976 After October 6, 1976. He went to Sweden, because political crisis.

-1981 He returned to Thailand. Are farmer in Nakorn Rachasima Province.

- 1992 Kamsing Srinok won the National Artist status

By Prasop Surapinit

Lao Kam Hom (ลาวคำหอม), is a low-profiled but powerful writer, whose short stories

recreate northeastern village life. He was born on 25 December 1930, in

Nakhorn Rachasima Province in Northeastern of Thailand. His most acclaimed

short story, Fa Bo Kan (ฟ้าบ่กั้น) is about the hardship the Northeasterners

must face during a cruel drought.

-1952 he worked as Forestry office in Chiang Mai Province.

-1958 he return to farmer in Nakorn Rachasima. ( PM. Sarit Thanarat)cruel

-1976 After October 6, 1976. He went to Sweden, because political crisis.

-1981 He returned to Thailand. Are farmer in Nakorn Rachasima Province.

- 1992 Kamsing Srinok won the National Artist status

By Prasop Surapinit

Death and Dying in the Theravadaby Ajahn Jagaro

More often than not in this society of ours, which is a life-affirming society, a beauty- and pleasure-affirming society, the topic of death and dying is avoided. Not only this society, but most societies, including traditional Buddhist cultures, avoid the topic of death as though it were something unpleasant, depressing, to be avoided; even a bad omen: "Don't talk about it as you may encourage it to happen!" Of course this attitude is not very wise and certainly not in keeping with the Buddhist attitude. So this evening I would like to speak on the Buddhist attitude to death and dying. Why think about it? First of all, why should we think about death? Why should we contemplate it? Not only did the Buddha encourage us to speak about death, he encouraged us to actually think about it, contemplate it and reflect on it regularly. On one occasion the Buddha asked several of the monks, "How often do you contemplate death?"One of them replied, "Lord, I contemplate death every day.""Not good enough," the Buddha said, and asked another monk, who replied,"Lord, I contemplate death with each mouthful that I eat during the meal.""Better, but not good enough," said the Buddha, "What about you?"The third monk said, "Lord, I contemplate death with each inhalation and each exhalation." That's all it takes, the inhalation comes in, it goes out, and one day it won't come in again - and that's it. That's all there is between you and death, just that inhalation, the next inhalation.Obviously the Buddha considered this a very important part of meditation and training towards becoming more wise and more peaceful. Why is it that this contemplation is encouraged? Because we don't usually want to think or talk about death. Be it conscious or unconscious, there is a fear of death, a tendency to avoid it, a reluctance to come face to face with this reality.Death is very much a part of life; it's just as much a part of life as birth. In fact, the moment of birth implies death. From the moment of conception it is only a matter of time before death must come - to everyone. No one can escape it. That which is born will die. The mind and body which arise at the time of conception develop, grow and mature. In other words, they follow the process of aging. We call it growing up at first, then growing old, but it's just a single process of maturing, developing, evolving towards the inevitable death. Everyone of you has signed a contract, just as I did. You may not remember signing that contract, but everyone has said, "I agree to die." Every living being, not only human, not only animal, but in every plane, in every realm, everywhere there is birth, there is the inevitable balance - death.Today, according to a book I read, about 200,000 people died. That is the average everyday. Apparently about 70 million people die every year. That's a lot of people isn't it? The population of Australia is only about 16 million and every year 70 million people die by various means, 200,000 in one day. That's an awful lot of people. But in our society we have very little contact with death. We are not usually brought face to face with death, we are not encouraged to contemplate death or come to terms with it.What we are usually encouraged to do is to avoid it and live as if we were never going to die. It is quite remarkable that intellectually we all know we are going to die, but we all live as if we are never going to die. This avoidance, this negation, usually means that we will always be afraid of death. As long as there is fear of death, life itself is not being lived at its best. So one of the very fundamental reasons for contemplating death, for making this reality fully conscious, is that of overcoming fear. The contemplation of death is not for making us depressed or morbid, it is rather for the purpose of helping to free us from fear. That's the first reason, which I will explain later in more detail.The second reason is that contemplation of death will change the way we live and our attitudes toward life. The values that we have in life will change quite drastically once we stop living as if we are going to live forever, and we will start living in a quite different way.The third reason is to develop the ability to approach death in the right way. By that I mean dying, the way we actually die.The contemplation of death has three benefits:relieving fear bringing a new quality to our lives, enabling us to live our lives with proper values, andenabling us to die a good death.It enables us to live a good life and die a good death. What more could you want? Being conscious of death First, let's look at the contemplation of death. This entails actually making oneself acknowledge death by consciously bringing into mind the fact: "I am going to die." You may say, "I know that." But you don't know it; not fully, not consciously.There should be many opportunities to do this contemplation, but in present day society there are not, simply because we are so far removed from death. We don't see it. Oh yes, you see it on television and at the movies, but it's all a game, you know they are only acting. It's only a game isn't it? You sit there and watch people being shot, hundreds of them, and it's only a game. This actually has the opposite effect. It makes you even less able to acknowledge the reality of death, because it's like a game, it's not real, it's reinforcing the perception that death is not real.We are very far removed from the experience of death, not because death is not to be found, but because of the way our society is structured. How many of you see death? How many of you see dying people? How many of you are present at the time of death? How many of you have the opportunity to sit with a corpse? Not many of you have that opportunity.But it doesn't matter how far removed you are, you can never be completely removed, because it is such an imposing reality, especially when someone in your family dies. Even so, most often it is taken away from you. People die in hospital. If they die at home you call the funeral directors and they take the body away and put it in the funeral parlour. If you have a service the body is all sealed up and then it is cremated for you.So you have very little contact, which is very different from the way things used to be. In earlier times, in more simple cultures, if a member of your family died you washed the corpse, dressed it, and burned it or buried it yourself. You had to do it; no one was going to come and do it for you. You, your family and your friends had to dress the body, carry it, collect the wood, make a pile and put the body on the pile of wood and burn it.This is how cremation was - very basic. In fact this is very much how we still cremate bodies in our forest monastery in Thailand. There we usually use a very simple coffin that the villagers make themselves. They just collect some planks, knock up a coffin, put the body in it - no lid - put it in the hall and everybody is there to see and contemplate it. Then they make a pile of logs, place the body on top, and burn it while everybody stands around and watches. So there is an opportunity to see the natural end of life, the end of one cycle of life. And that has a very good effect in helping us to rise up and come to terms with this reality, rather than it being a ghost, a skeleton in the closet waiting to sneak out and haunt you.Anything that is not brought out and fully confronted, fully come to term with, can have power over you. Ghosts usually haunt at night when you can't see them. They sneak up behind you when you're not looking and can't see them. When you put on the light there is no ghost. In order to have power over us, to make us frightened, it must be something that we can't face, something that we can't fully, consciously, clearly see. It must remain unknown and mysterious. As long as we allow death to remain that way it will bring fear into our hearts.But through contemplation, through attention and consciously finding ways of bringing this fact into the mind and coming to terms with it, fear can be overcome. This is why the contemplation of death is one of the main contemplations in Buddhism. It can be done in many ways. Most mornings in our monastery we chant one particular reflection which goes:I am of the nature to age, I have not gone beyond aging. I am of the nature to sicken, I have not gone beyond sickness. I am of the nature to die, I have not gone beyond dying. All that is mine, beloved and pleasing, will change, will become otherwise, will become separated from me.When you contemplate this reality with a peaceful mind and really bring it into consciousness, it has a powerful effect in overcoming the fear of old age, sickness, death and separation. It's not for making us morbid, it's for freeing us from fear. That is why we contemplate death: it's not that we are looking forward to dying, but that we want to live and die without fear. So to have an opportunity to be with a dead body is to be encouraged. It's good if you have such an opportunity to actually sit and be with the body, to actually witness the end of a human life, to ask yourself, "Is this death?"When you die, you can't take anything with you - not even your own body. In Buddhist monasteries this is considered so important that quite often skeletons are displayed in the meditation hall. In one monastery there was a monk who left instructions that after his death his body, fully robed and sitting in full lotus, was to be put in a glass case. There he sat slowly disintegrating. Written on the front of the glass case was: "I used to be like you; soon you will be like me." Now when you see that, it has quite a powerful impact. It's a fact you just can't escape.The fact is that every single person is going to die. This is not a prediction I'm making through clairvoyant powers. It's just the inescapable fact that because you're born, you're going to die. All that remains to be known is the time: when is it going to happen? That's the unknown factor. The fact that you are going to die is not questionable, it is reality.So we contemplate. When there is death it's good to come into contact with it. Someone who was living perhaps ten minutes ago is now dead. Yes, that's what's going to happen to me, too. Even if there is no body, no corpse in sight, one can do this just sitting quietly, just making that thought very clear in one's mind. "I am going to die. I am going to die and I am going to have to leave everything behind, every single thing, every mortal being is going to be left behind."Now remember the purpose of this. It is to force the mind to come to terms with this reality. Quite often you will feel fear. There is still fear because you haven't accepted it yet. That's the purpose of the contemplation: to allow the fear to arise so that we can learn to transcend it, to get above this fear and to be able to acknowledge death without fear.Buddhist monks see a great variety of life. People often think the opposite, that because we're monks we're removed from the realities of life, that we're protected and sheltered, that we live in a remote realm where we don't really know what life's about. In a certain sense that may be true, but in another sense we have more contact with many aspects of life than most people do. This is because the role of monk within a community of people is to act as a spiritual guide and refuge. When there's a birth, everybody brings the baby to the monk and he gives a blessing. The monk experiences what it is for everyone to be happy. When someone is sick: 'Get the monk.' So the monk has very close contact with sickness, pain and fear.When there is death it is very important for the monk to be there, because most people are terrified of death, both those who are dying and those around them. People feel at a loss: 'What do we do?' As a monk I find that I have many occasions to come into contact with these things, both the pleasant and the unpleasant. I have found death to be one of the most rewarding experiences. I have also found it to be one of the most meaningful ways to be of service to others, because that is the time that I feel most useful. You may think that I feel most useful when I'm teaching meditation or giving these talks, but I really feel most useful in situations where there is death. That is the time when I feel that through my contemplation, through my appreciation of this process called life, I can be a refuge for the dying and for the people around the dying. As I said, it is also rewarding as a learning experience, especially the first few occasions when I had to be with someone who was actually dying.So there are opportunities for us to contemplate, to bring into the mind this part of life which is normally avoided. Notice if fear arises. If fear does arise, it must be dealt with, we must rise above it. How do we rise above the fear of death? The first thing is to acknowledge its inevitability. Everything, both animate and inanimate, follows the same process. It is just part of life, there is no problem.It's not that we look forward to it. Some people respond to this with, "Well, if you're not afraid of death, why don't you go and kill yourself?" But we're not afraid of living, either. Just because you're not afraid of something, does that mean that you have to do it? This rising up and acknowledging is part of life. Inevitably, I'm going to die - everybody, every plant, every tree, every insect, every form, every being, follows the same path. Soon it will be autumn, the leaves fall off the trees. We don't cry, it's natural, that's what the leaves are supposed to do at the end of the season. Human beings do the same thing. We have to rise to this occasion and acknowledge this reality.Another quality that is very helpful is confidence. Religious people usually have less fear of death than very materialistic people, because for the materialist there is only one life and that is it. Death is zero - finish - kaput! Of course to some people that's quite appealing, but for most people the thought that's it's all gone is not very desirable, in fact it's quite frightening.But from the Buddhist perspective, death is never seen as the end. From the Buddhist perspective birth is not the beginning and death is not the end. It's just one part of a whole process, a whole cyclic process of birth, death, rebirth, dying again, rebirth, dying again... If one has some appreciation or understanding of that, death begins to lose its sting, because it's not final, it's not really the end. It is only the end of a cycle. Just one cycle along the way and then the way continues with another cycle. The leaves fall off the trees, but it's not the end. They go back to the soil and nourish the roots, next year the tree has new leaves. There's no disappearance into nothing. The same can be said of human life. There are bodies, there are living beings, but death is not the end. Conditioned by the moment of death is rebirth. An appreciation of that helps to relieve a lot of the fear about death.So we bring up the thought of death, we sit and bring it to mind. If fear arises, then we try to rise above that fear so that the mind comes to terms and is at peace with reality. Living consciously Now this really does free us up, enabling us to live our lives more fully. The contemplation of death, rather than making us depressed and morbid, can actually help us live our lives more fully, with more joy, with more gratitude and appreciation. If we live our lives as though we were going to live forever, we don't appreciate them. We take them for granted and live in a very foolish and heedless way. We all live in foolish ways, simply because we don't consciously contemplate the fact of death.How do we live our lives in foolish ways? Just consider how much time we waste. For a start, how much time have we wasted today worrying about next year, about the next twenty years, thinking about the future, so that we are not fully living this day: "I'm looking forward to Wednesday. Then two more days to go... Thursday, Friday... then it's Saturday. I'll go to the football, the cricket. Sunday morning... meditation at the Buddhist Society. Great, I'm really looking forward to that."That's the mentality of our Australian society. Five days of the week are spent waiting for the weekend. So you live two days out of seven. Most people just endure five days of the week. From nine to five is a dreary existence, then in the evening they live for a couple of hours. We don't really appreciate life. We don't live our lives fully. We take it all so much for granted, as if we're going to make it till Saturday. You may not make it till Saturday! I may not make it till Saturday. If you or I really aren't going to make it till Saturday, we'd better make the best of today.This is how the contemplation of death helps to break this habitual way of living, where we take so much of life for granted, constantly overlooking the present and looking to the future. That is one of the foolish aspects of the way we live when we're not contemplating the reality of death.Another, which is even worse, concerns some of the things we do to each other. We can be very cruel and mean, holding on to hatred and resentment: "Oh well, let him stew for a few more days." Or: "Let her suffer for a few days, I'll apologise next Sunday." We do a lot of things to each other in unskilful ways in the expectation that next time we can fix it up."Next week, next month, I'll smooth it over." But what if there is no next month, no next week? What if there is no tomorrow? Suppose you have an argument today? You may die tonight, she may die tonight. You really wouldn't want to part having some terrible argument as your last memory, would you? It's better to apologise now before it's too late.You see again how we take for granted that there is always going to be a tomorrow. "But," you say, "I'm sure I'm not going to die tonight." Well, maybe not tonight, but one night or one day. It is so uncertain. It really is uncertain, you really don't know - 200,000 die today, tomorrow another 200,000. There is no guarantee that it won't be one of us.Has this every happened to you? You say, "I'll have to go and see so-and-so," taking it for granted that you will be able to see them. This happened to me with the person whose skeleton now hangs in the meditation hall at Wat Pah Nanachat. The skeleton is of a lay-supporter who used to come to the monastery, but then she developed cancer, which caused her a great deal of suffering. I used to visit her regularly, and one day I had intended visiting her as I was coming back from the town to the monastery, but I thought, "Oh, not today, maybe tomorrow." I was feeling a bit tired, so I thought I'd visit her in a few days time. She died, and I really regretted that I hadn't dropped in. I had assumed that she would be around the day after. That can happen to all of us. If we really recognise that, if we can bring that consciously into our minds, it can help us live our lives a little more wisely, by not leaving unfinished business, negative experiences, resentment, hatred and conflict to linger.I've seen this in practice. For sixteen years my father and I were not on good terms. He resented my wearing this robe and was very unhappy being unable to come to terms with it. He'd also had an argument with his brother, before I was born, and they had not spoken to each other since. My father's brother lived in Italy and the feud between them started before my father left Italy. They wouldn't speak to each other at all, and this went on for thirty or forty years. Then one year my father changed quite radically, quite drastically. One of the factors for this change may have been something I said to him. I said, "If you are not going to change your view about me, then you're going to suffer for the rest of your life, until the day you die." I think that had quite an impact, as he was getting old. At that time he was 74 or 75. He recognised that he was going to die, it became a conscious reality.So he decided to set his home straight. He made peace with me. He went to Italy and resolved the argument with his brother that had being going for forty years. He settled all the financial matters that had been left pending for about fifteen years or so and he came back. I remember him saying to me, "I don't want to die with any of these unfinished things on my mind. I want to die peacefully."That's the effect of contemplating the reality of death. It makes us live more wisely, resolving these unfinished matters. Don't let them linger: the fights, the hatred, the conflicts, the feuds, the debts, whatever. We have the chance, let's get it in order. That's very important. That's a benefit of contemplating death, it affects the way we live our lives. We live them more fully, with gratitude. We don't let things linger on, we don't leave unfinished business.And our values in life will change. What is important in life? What is motivating you? What is the drive in your life? If we really contemplate death it may cause us to reconsider our values. It doesn't matter how much money you've got, you can't take any of it with you. It's true about everybody, about every religion. You can't take anything at all with you. Whether you have a million dollars or just ten cents, you can't take it with you. Your own body has to be left for others to dispose of in one way or another, it's just refuse left behind. You can't take your body with you, you can't take your wealth with you, you can't take your cars or your houses with you; we can't even take our Buddhist temples with us. That should make us consider how important these things are to us. What is important in our lives then? Is there anything that we take with us? What do we take with us? What is important? Maybe the quality of life is more important than material acquisitions. The quality of life is primarily the quality of our minds. How we are living today may be more important than a lot of these other things. Considering that the Buddhist perspective of death is not the end, but the condition for rebirth, and that rebirth is conditioned by death and the quality of the mind, there is one thing you take with you. There is one inheritance that you don't leave behind for others:I am the owner of my kamma, heir to my kamma, Born of my kamma, related to my kamma, abide supported by my kamma. Whatever kamma I shall do, for good or for ill, of that I will be the heir.That is all that follows, the qualities that we develop within us, the qualities of mind and heart, the spiritual qualities, the good or bad qualities. This is what we inherit. This is what conditions rebirth and shapes the future. So again this gives rise to a new value in our lives. The contemplation of death may change our values. Then we may not think it so important to strive so hard to make that extra million. We may not live long enough to enjoy it; we may as well enjoy the million we've already got, living more peacefully and starting to build up some spiritual qualities. It can have a very good effect on the way we live our lives and on the values we develop. It's not just a matter of being successful, it's how we become successful. What we're developing within us is more important than becoming successful.I was giving a talk the other evening to a group of people. In the audience there were quite a few young people and a question was asked about the relevance of Buddhism in this competitive society. I said I don't mind competition, I think competition is good. As long as competition doesn't mean abandoning your humanity, competition is fine. However, it should not be at the expense of your humanity, of the humane qualities of virtue and compassion. You can still compete, you can still strive, but not at the expense of these qualities, because ultimately these are more important. They are your true inheritance. Whether you succeed in getting that business deal or not, whether you make that $100,000 or not, whether you get that new car ten thousand dollars cheaper or not, seems so important in the short term. Ten thousand dollars is a lot of money, but if you have to do that at the expense of your humanity, your moral principles, your virtue and your compassion, it's not worth it, because you'll have to leave the money behind sooner or later - perhaps sooner than you expect. Your only inheritance is the quality of your mind.This contemplation of death can help us to live our lives with more gratitude, with less fear, with more immediacy and with values that are really important. That is why we encourage contemplation of death and the process of dying. Dying peacefully Having considered all of this, if dying becomes no longer a contemplation but an actual experience, we can face it without fear. Not only can we face it without fear, we can also do a lot towards dying a good death. If we have led a good life, dying is easier. But regardless of how we have lived, we can still endeavour to die a good death. To help in the dying process, we stress very much the evelopment of the same quality of fearlessness. Death is not to be feared, it's just natural.The fear of death is often connected to the fear of pain. For many people it's more the fear of pain and the fear of separation from all that is loved that is fearsome. At the time of dying encouragement and reassurance are essential. For a start you need to reassure yourself. The pain is difficult to bear, but we are fortunate in that modern medicines make it possible to reduce the amount of physical pain a human being has to experience at death. Pain need not be such an overwhelming object of fear.I usually reassure a dying person, such as someone who has cancer, that they won't be allowed to suffer, that they won't have to endure excruciating pain, that they will be given medicine. They certainly should be given medicine to alleviate the pain. An important result of this is that they can relax and die more peacefully.The other worry is the separation from loved ones, from one's possessions. Of course, if we've contemplated this before, it's a lot easier. We know that to come together implies separation. That's all life is, a meeting and a separation. I came to Melbourne two months ago, in a few days I'll be leaving. That's just the way it is. If we contemplate that, it won't be so frightening to us. If a dying person hasn't done this kind of contemplation, then you need to gently encourage and reassure him or her that the children and those left behind will be taken care of. They need to be reassured that it's all right, that there are friends to take care of them, they need to be encouraged to relax and be peaceful, not to worry about other things, that they'll all be taken care of.The whole emphasis is on trying to encourage the dying person, be it oneself or another, to become more peaceful. How can you die a good death? By becoming more peaceful. The Buddhist way is to try and maintain an atmosphere of peace in the room where someone is dying. It's not very good to have people shouting and screaming, waving and crying and tugging and pulling. What does that do to the poor person who has this very important thing to do, to die? They make it very difficult to die peacefully. Give those present time to become quiet. It is good if friends and relatives are present, people who can show by their presence that they care, that they love, that they are willing to let go, to reassure, to offer support - that's enough.Symbols are very useful. If the dying person is a Buddhist, then a Buddha statue, and possibly the presence of Buddhist monks, soothing words and teachings to allow the person to give up their life with the greatest peace and dignity, is very beneficial. It's a wonderful thing for them to move into their new life in the best possible way.So these are some reflections with regard to death and dying. There are many other aspects to this topic that I could cover but I don't want to go beyond my allotted time. There are a few stories from the Buddha that illustrate very much what I've been saying. The classic one, which I tell at every funeral, is the story about Kisagotami, a woman who lived during the time of the Buddha. She had a baby son of whom she was very proud. Now this little boy got very sick and died. Kisagotami was so disturbed, so distressed by his death that she became a little mentally unhinged. She could not accept the fact that her baby had died. "No, it's only sick, I need medicine. I have to have medicine to cure my baby." She went from place to place, from home to home, from friend to friend, but no one could help her. They told her the baby was dead, but she couldn't accept this and kept asking for medicine.Finally she went to the Buddha because she had heard that he was a spiritual teacher with great psychic powers. She asked the Buddha, "Please give me some medicine to cure my baby." The Buddha said, "Put the baby down here, I will cure your baby provided you can get a few mustard seeds for me. But you must get these mustard seeds from a home where there has never been a death."So she went running off into the town and went to the first house, where she asked for mustard seeds. Being a common commodity of little value they were promptly offered to her. As she was about to accept the mustard seeds she asked, "Has there ever been a death in this home?" Of course the reply was, "Oh yes, only a few months ago so-and-so died." She went from home to home and the experience was exactly the same. This gradually had an effect on her.When she came towards the end of the village realisation finally pushed through her demented state of mind: death is everywhere; in every home there is death. Death is part of life. She was able to recognise this fact and come to terms with reality. She went back to the Buddha who asked her, "Kisagotami, did you get the mustard seeds?" "Enough of mustard seeds, Lord," she replied, and took her baby and cremated it. She came back and became a Buddhist nun and not long afterwards becameenlightened.I like this story because it represents the Buddhist approach to death. Rather than bringing the baby back to life, the Buddhist way is to acknowledge the reality of death. Being a reality, it must be accepted. We don't look for death, but we don't fear it; we don't ask for death, but we're willing to accept it when it comes. Through the understanding that comes from this contemplation of death, we can live good lives with skilful values, with true appreciation, and we can die a good death, peacefully. http://www.katinkahesselink.net/tibet/death_jagaro.html |

Death & Dying in the MahayanaDeath & Dying in Tibetan Tradition. Contemplation and meditation on death and impermanence are regarded as very important in Buddhism for two reasons : (1) it is only by recognising how precious and how short life is that we are most likely to make it meaningful and to live it fully and (2) by understanding the death process and familiarizing ourself with it, we can remove fear at the time of death and ensure a good rebirth.

Because the way in which we live our lives and our state of mind at death directly influence our future lives, it is said that the aim or mark of a spiritual practitioner is to have no fear or regrets at the time of death. People who practice to the best of their abilities will die, it is said, in a state of great bliss. The mediocre practitioner will die happily. Even the initial practitioner will have neither fear nor dread at the time of death. So one should aim at achieving at least the smallest of these results. There are two common meditations on death in the Tibetan tradition. The first looks at the certainty and imminence of death and what will be of benefit at the time of death, in order to motivate us to make the best use of our lives. The second is a simulation or rehearsal of the actual death process, which familiarizes us with death and takes away the fear of the unknown, thus allowing us to die skilfully. Traditionally, in Buddhist countries, one is also encouraged to go to a cemetery or burial ground to contemplate on death and become familiar with this inevitable event. The first of these meditations is known as the nine-round death meditation, in which we contemplate the three roots, the nine reasonings, and the three convictions, as described below: A. Death is Certain 1. There is no possible way to escape death. No-one ever has, not even Jesus, Buddha, etc. Of the current world population of over 5 billion people, almost none will be alive in 100 years time. 2. Life has a definite, inflexible limit and each moment brings us closer to the finality of this life. We are dying from the moment we are born. 3. Death comes in a moment and its time is unexpected. All that separates us from the next life is one breath. Conviction: To practise the spiritual path and ripen our inner potential by cultivating positive mental qualities and abandoning disturbing mental qualities. B. The Time of Death is Uncertain 4. The duration of our lifespan is uncertain. The young can die before the old, the healthy before the sick, etc. 5. There are many causes and circumstances that lead to death, but few that favour the sustenance of life. Even things that sustain life can kill us, for example food, motor vehicles, property. 6. The weakness and fragility of one's physical body contribute to life's uncertainty. The body can be easily destroyed by disease or accident, for example cancer, AIDS, vehicle accidents, other disasters. Conviction: To ripen our inner potential now, without delay. C. The Only Thing That Can Help Us At The Time Of Death Is OUr Mental/Spiritual Development (because all that goes on to the next life is our mind with its karmic (positive or negative) imprints.) 7. Worldly possessions such as wealth, position, money can't help 8. Relatives and friends can neither prevent death nor go with us. 9. Even our own precious body is of no help to us. We have to leave it behind like a shell, an empty husk, an overcoat. Conviction: To ripen our inner potential purely, without staining our efforts with attachment to worldly concerns. The second meditation simulates or rehearses the actual death process. Knowledge of this process is particularly important because advanced practitioners can engage in a series of yogas that are modelled on death, intermediate state (Tibetan: bar-do) and rebirth until they gain such control over them that they are no longer subject to ordinary uncontrolled death and rebirth. It is therefore essential for the practitioner to know the stages of death and the mind-body relationship behind them. The description of this is based on a presentation of the winds, or currents of energy, that serve as foundations for various levels of consciousness, and the channels in which they flow. Upon the serial collapse of the ability of these winds to serve as bases of consciousness, the internal and external events of death unfold. Through the power of meditation, the yogi makes the coarse winds dissolve into the very subtle life-bearing wind at the heart. This yoga mirrors the process that occurs at death and involves concentration on the psychic channels and the channel-centres (chakras) inside the body. At the channel-centres there are white and red drops, upon which physical and mental health are based. The white is predominant at the top of the head and the red at the solar plexus. These drops have their origin in a white and red drop at the heart centre, and this drop is the size of a small pea and has a white top and red bottom. It is called the indestructible drop, since it lasts until death. The very subtle life-bearing wind dwells inside it and, at death, all winds ultimately dissolve into it, whereupon the clear light vision of death dawns. The physiology of death revolves around changes in the winds, channels and drops. Psychologically, due to the fact that consciousnesses of varying grossness and subtlety depend on the winds, like a rider on a horse, their dissolving or loss of ability to serve as bases of consciousness induces radical changes in conscious experience. Death begins with the sequential dissolution of the winds associated with the four elements (earth, water, fire and air). "Earth" refers to the hard factors of the body such as bone, and the dissolution of the wind associated with it means that that wind is no longer capable of serving as a mount or basis for consciousness. As a consequence of its dissolution, the capacity of the wind associated with "water" (the fluid factors of the body) to act as a mount for consciousness becomes more manifest. The ceasing of this capacity in one element and its greater manifestation in another is called "dissolution" - it is not, therefore, a case of gross earth dissolving into water. Simultaneously with the dissolution of the earth element, four other factors dissolve (see Chart 1), accompanied by external signs (generally visible to others) and an internal sign (the inner experience of the dying person). The same is repeated in serial order for the other three elements (see Charts 2-4), with corresponding external and internal signs. Upon the inception of the fifth cycle the mind begins to dissolve, in the sense that coarser types cease and subtler minds become manifest. First, conceptuality ceases, dissolving into a mind of white appearance. This subtler mind, to which only a vacuity filled by white light appears, is free from coarse conceptuality. It, in turn, dissolves into a heightened mind of red appearance, which then dissolves into a mind of black appearance. At this point all that appears is a vacuity filled by blackness, during which the person eventually becomes unconscious. In time this is cleared away, leaving a totally clear emptiness (the mind of clear light) free from the white, red and black appearances (see Chart 5). This is the final vision of death. This description of the various internal visions correlates closely with the literature on the near-death experience. People who have had a near-death experience often describe moving from darkness (for example a black tunnel) towards a brilliant, peaceful, loving light. A comprehensive study comparing death and near-death experiences of Tibetans and Euro-Americans has shown many similarities between the two (Carr, 1993). Care must be taken though in such comparisons because the near-death experience is not actual death, that is, the consciousness permanently leaving the body. Since the outer breath ceased some time before (in the fourth cycle), from this point of view the point of actual death is related not to the cessation of the outer breath but to the appearance of the mind of clear light. A person can remain in this state of lucid vacuity for up to three days, after which (if the body has not been ravaged by illness) the external sign of drops of red or white liquid emerging from the nose and sexual organ occur, indicating the departure of consciousness. Other signs of the consciousness leaving the body are 1) when all heat has left the area of the heart centre (in the centre of the chest), 2) the body starts to smell or decompose, 3) a subtle awareness that the consciousness has left and the body has become like 'an empty shell', 4) a slumping of the body in a practitioner who has been sitting in meditation after the stopping of the breath. Buddhists generally prefer that the body not be removed for disposal before one or more of these signs occur, because until then the consciousness is still in the body and any violent handling of it may disturb the end processes of death. A Buddhist monk or nun or friend should ideally be called in before the body is moved in order for the appropriate prayers and procedures to be carried out. When the clear light vision ceases, the consciousness leaves the body and passes through the other seven stages of dissolution (black near-attainment, red increase etc.) in reverse order. As soon as this reverse process begins the person is reborn into an intermediate state between lives, with a subtle body that can go instantly wherever it likes, move through solid objects etc., in its journey to the next place of rebirth. The intermediate state can last from a moment to seven days, depending on whether or not a suitable birthplace is found. If one is not found the being undergoes a "small death", experiencing the eight signs of death as previously described (but very briefly). He/she then again experiences the eight signs of the reverse process and is reborn in a second intermediate state. This can happen for a total of seven births in the intermediate state (making a total of forty-nine days) during which a place of rebirth must be found. The "small death" that occurs between intermediate states or just prior to taking rebirth is compared to experiencing the eight signs (from the mirage-like vision to the clear light) when going into deep sleep or when coming out of a dream. Similarly also, when entering a dream or when awakening from sleep the eight signs of the reverse process are experienced. These states of increasing subtlety during death and of increasing grossness during rebirth are also experienced in fainting and orgasm as well as before and after sleeping and dreaming, although not in complete form. It is this great subtlety and clarity of the mind during the death process that makes it so valuable to use for advanced meditation practices, and why such emphasis is put on it in Buddhism. Advanced practitioners will often stay in the clear light meditation for several days after the breathing has stopped, engaging in these advanced meditations, and can achieve liberation at this time. The Buddhist view is that each living being has a continuity or stream of consciousness that moves from one life to the next. Each being has had countless previous lives and will continue to be reborn again and again without control unless he/she develops his/her mind to the point where, like the yogis mentioned above, he/she gains control over this process. When the stream of consciousness or mind moves from one life to the next it brings with it the karmic imprints or potentialities from previous lives. Karma literally means "action", and all of the actions of body, speech and mind leave an imprint on the mind-stream. These karmas can be negative, positive or neutral, depending on the action. They can ripen at any time in the future, whenever conditions are suitable. These karmic seeds or imprints are never lost. At the time of death (clear light stage) the consciousness (very subtle mind) leaves the body and the person takes the body of an intermediate state being. They are in the form that they will take in their next life (some texts say the previous life), but in a subtle rather than a gross form. As mentioned previously, it can take up to forty-nine days to find a suitable place of rebirth. This rebirth is propelled by karma and is uncontrolled. In effect the karma of the intermediate state being matches that of its future parents. The intermediate state being has the illusory appearance of its future parents copulating. It is drawn to this place by the force of attraction to its parent of the opposite sex, and it is this desire that causes the consciousness of the intermediate state being to enter the fertilized ovum. This happens at or near the time of conception and the new life has begun. One will not necessarily be reborn as a human being. Buddhists describe six realms of existence that one can be reborn into, these being the hell realms, the preta (hungry ghost) realm, the animal realm, the human realm, the jealous god (asura) realm and the god (sura) realms. One's experience in these situations can range from intense suffering in the hell realms to unimaginable pleasures in the god realms. But all of these levels of existence are regarded as unsatisfactory by the spiritual practitioner because no matter how high one goes within this cyclic existence, one may one day fall down again to the lower realms of existence. So the aim of the spiritual practitioner is to develop his/her mind to the extent where a stop is put to this uncontrolled rebirth, as mentioned previously. The practitioner realises that all six levels of existence are ultimately in the nature of suffering, so wishes to be free of them forever. The state of mind at the time of death is regarded as extremely important, because this plays a vital part in the situation one is reborn into. This is one reason why suicide is regarded in Buddhism as very unfortunate, because the state of mind of the person who commits suicide is usually depressed and negative and is likely to throw them into a lower rebirth. Also, it doesn't end the suffering, it just postpones it to another life. When considering the spiritual care of the dying, it can be helpful to divide people into several different categories, because the category they are in will determine the most useful approach to use. These categories are: 1) whether the person is conscious or unconscious, and 2) whether they have a religious belief or not. In terms of the first category, if the person is conscious they can do the practices themselves or someone can assist them, but if they are unconscious someone has to do the practices for them. For the second category, if a person has specific religious beliefs, these can be utilised to help them. If they do not, they still need to be encouraged to have positive/virtuous thoughts at the time of death, such as reminding them of positive things they have done during their life. For a spiritual practitioner, it is helpful to encourage them to have thoughts such as love, compassion, remembering their spiritual teacher. It is beneficial also to have an image in the room of Jesus, Mary, Buddha, or some other spiritual figure that may have meaning for the dying person. It may be helpful for those who are with the dying person to say some prayers, recite mantras etc. - this could be silent or aloud, whatever seems most appropriate. However, one needs to be very sensitive to the needs of the dying person. The most important thing is to keep the mind of the person happy and calm. Nothing should be done (including certain spiritual practices) if this causes the person to be annoyed or irritated. There is a common conception that it is good to read "The Tibetan Book of the Dead" to the dying person, but if he/she is not familiar with the particular deities and practices contained in it, then this is not likely to prove very beneficial. Because the death process is so important, it is best not to disturb the dying person with noise or shows of emotion. Expressing attachment and clinging to the dying person can disturb the mind and therefore the death process, so it is more helpful to mentally let the person go, to encourage them to move on to the next life without fear. It is important not to deny death or to push it away, just to be with the dying person as fully and openly as possible, trying to have an open and deep sharing of the person's fear, pain, joy, love, etc. As mentioned previously, when a person is dying, their mind becomes much more subtle, and they are more open to receiving mental messages from those people close to them. So silent communication and prayer can be very helpful. It is not necessary to talk much. The dying person can be encouraged to let go into the light, into God's love etc. (again, this can be verbal or mental). It can be very helpful to encourage the dying person to use breathing meditation - to let go of the thoughts and concentrate on the movement of the breath. This can be helpful for developing calmness, for pain control, for acceptance, for removing fear. It can help the dying person to get in touch with their inner stillness and peace and come to terms with their death. This breathing technique can be especially useful when combined with a mantra, prayer, or affirmation (i.e. half on the in-breath, half on the out-breath). One of the Tibetan lamas, Sogyal Rinpoche, says that for up to about twenty-one days after a person dies they are more connected to the previous life than to the next one. So for this period in particular the loved ones can be encouraged to continue their (silent) communication with the deceased person - to say their good-byes, finish any unfinished business, reassure the dead person, encourage them to let go of their old life and to move on to the next one. It can be reassuring even just to talk to the dead person and at some level to know that they are probably receiving your message. The mind of the deceased person at this stage can still be subtle and receptive. For the more adept practitioners there is also the method of transference of consciousness at the time of death (Tibetan: po-wa). With training, at the time of death, the practitioner can project his mind upwards from his heart centre through his crown directly to one of the Buddha pure realms, or at least to a higher rebirth. Someone who has perfected this training can also assist others at the time of death to project their mind to a good rebirth. It is believed that if the consciousness leaves the body of the dead person through the crown or from a higher part of the body, it is likely to result in a good type of rebirth. Conversely, if the consciousness leaves from a lower part of the body this is likely to result in rebirth in one of the lower realms. For this reason, when a person dies it is believed that the first part of the body that should be touched is the crown. The crown is located about eight finger widths (of the person being measured) back from the (original) hairline. To rub or tap this area or gently pull the crown hair after a person dies is regarded as very beneficial and may well help the person to obtain a higher rebirth. Their are special blessed pills (po-wa pills) that can be placed on the crown after death which also facilitates this process. Once the consciousness has left the body (which, as mentioned earlier, can take up to three days) it doesn't matter how the body is disposed of or handled (including the carrying out of a post-mortem examination) because in effect it has just become an empty shell. However, if the body is disposed of before the consciousness has left, this will obviously be very disturbing for the person who is going through the final stages of psychological dissolution. This raises the question of whether or not it is advisable to donate one's organs after dying. The usual answer given by the Tibetan lamas to this question is that if the wish to donate one's organs is done with the motivation of compassion, then any disturbance to the death process that this causes is far outweighed by the positive karma that one is creating by this act of giving. It is another way in which one can die with a positive and compassionate mind. A Tibetan tradition which is becoming more popular in the West is to get part of the remains of the deceased (e.g. ashes, hair, nails) blessed and then put into statues, tsa-tsas (Buddha images made of clay or plaster) or stupas (reliquary monuments representing the Buddha's body, speech and mind). These stupas for instance could be kept in the person's home, larger ones could be erected in a memorial garden. Making offerings to these or circumambulating them and so on is regarded as highly meritorious, both for the person who has died and for the loved ones. There are also rituals for caring for the dead, for guiding the dead person through the intermediate state into a good rebirth. Such a ritual is "The Tibetan Book of the Dead", more correctly titled "Liberation Through Hearing in the Bardo". |

วันออกพรรษา

วันออกพรรษา [วัน-ออก-พัน-สา]

wan-òk-pan-săa

N. the end of Buddhist lent

[วันที่สิ้นการจำพรรษาแห่งพระสงฆ์ คือ วันขึ้น 15 ค่ำเดือน 11]

หลังเทศกาลเข้าพรรษาผ่านพ้นไปได้ 3 เดือน ก็จะเป็น วันออกพรรษา ซึ่งถือเป็นการสิ้นสุดระยะการจำพรรษา โดย

วันออกพรรษา ตรงกับวันขึ้น 15 ค่ำ เดือน 11 ของทุกปี ปีนี้ วันออกพรรษา ตรงกับวันที่ 12 ตุลาคม 2554 เมื่อทำพิธี

วันออกพรรษา แล้ว พระภิกษุสงฆ์สามารถจาริกไปในสถานที่ต่าง ๆ หรือค้างคืนที่อื่นได้โดยไม่ผิดพระพุทธบัญญัติ

มีโอกาสได้อนุโมทนากฐิน

ประเพณีเกี่ยวข้องกับวันออกพรรษา

1. ประเพณีตักบาตรเทโว หลัง วันออกพรรษา 1 วัน คือ แรม 1 ค่ำ เดือน 11 จะมีการ "ตักบาตรเทโว"

จังหวัดนครปฐม ที่พระปฐมเจดีย์ พระภิกษุสามเณรจะมารวมกันที่องค์พระปฐมเจดีย์ แล้วก็เดินลงมาจากบันไดนาคหน้าวิหารพระร่วง สมมติว่าพระเดินลงมาจาก

บันไดสวรรค์ชาวบ้านก็คอยใส่บาตร

จังหวัดอุทัยธานี ซึ่งตั้งอยู่บนยอดเขาสูง ณ วัดสะแกกรัง พระภิกษุก็จะเดินลงมาจากเขารับบิณฑบาตจากชาวบ้านโดยขบวนพระภิกษุสงฆ์ที่ลงมาจากบันไดนั้น

นิยมให้มีพระพุทธรูปนำหน้า ทำการสมมติว่าเป็นพระพุทธเจ้า จะใช้พระปางอุ้มบาตร ห้ามมาร ห้ามสมุทร รำพึง ถวายเนตรหรือปางลีลา ตั้งไว้บนรถหรือตั้งบน

คานหาม มีที่ตั้งบาตร สำหรับอาหารบิณฑบาต

wan-òk-pan-săa

N. the end of Buddhist lent

[วันที่สิ้นการจำพรรษาแห่งพระสงฆ์ คือ วันขึ้น 15 ค่ำเดือน 11]

หลังเทศกาลเข้าพรรษาผ่านพ้นไปได้ 3 เดือน ก็จะเป็น วันออกพรรษา ซึ่งถือเป็นการสิ้นสุดระยะการจำพรรษา โดย

วันออกพรรษา ตรงกับวันขึ้น 15 ค่ำ เดือน 11 ของทุกปี ปีนี้ วันออกพรรษา ตรงกับวันที่ 12 ตุลาคม 2554 เมื่อทำพิธี

วันออกพรรษา แล้ว พระภิกษุสงฆ์สามารถจาริกไปในสถานที่ต่าง ๆ หรือค้างคืนที่อื่นได้โดยไม่ผิดพระพุทธบัญญัติ

มีโอกาสได้อนุโมทนากฐิน

ประเพณีเกี่ยวข้องกับวันออกพรรษา

1. ประเพณีตักบาตรเทโว หลัง วันออกพรรษา 1 วัน คือ แรม 1 ค่ำ เดือน 11 จะมีการ "ตักบาตรเทโว"

จังหวัดนครปฐม ที่พระปฐมเจดีย์ พระภิกษุสามเณรจะมารวมกันที่องค์พระปฐมเจดีย์ แล้วก็เดินลงมาจากบันไดนาคหน้าวิหารพระร่วง สมมติว่าพระเดินลงมาจาก

บันไดสวรรค์ชาวบ้านก็คอยใส่บาตร

จังหวัดอุทัยธานี ซึ่งตั้งอยู่บนยอดเขาสูง ณ วัดสะแกกรัง พระภิกษุก็จะเดินลงมาจากเขารับบิณฑบาตจากชาวบ้านโดยขบวนพระภิกษุสงฆ์ที่ลงมาจากบันไดนั้น

นิยมให้มีพระพุทธรูปนำหน้า ทำการสมมติว่าเป็นพระพุทธเจ้า จะใช้พระปางอุ้มบาตร ห้ามมาร ห้ามสมุทร รำพึง ถวายเนตรหรือปางลีลา ตั้งไว้บนรถหรือตั้งบน

คานหาม มีที่ตั้งบาตร สำหรับอาหารบิณฑบาต

พิธีชักพระทางบก

พิธีชักพระทางบก

ในจังหวัดนครศรีธรรมราช ก่อนวันชักพระ 2 วัน จะมีพิธีใส่บาตรหน้าล้อ นอกจากอาหารคาวหวานแล้ว ยังมี

สิ่งที่เป็นสัญลักษณ์ของงาน คือ "ปัด" หรือข้าวต้มผัดน้ำกะทิห่อด้วยใบมะพร้าว บางที่ห่อด้วยใบกะพ้อ

(ปาล์มชนิดหนึ่ง) ในภาคกลางเขาเรียกว่า ข้าวต้มลูกโยน ก่อนจะถึงวันออกพรรษา 1 - 2 สัปดาห์ ทางวัด

จะทำเรือบก คือ เอาท่อนไม้ขนาดใหญ่ 2 ท่อนมาทำเป็นพญานาค 2 ตัว เป็นแม่เรือที่ถูกยึดไว้อย่างแข็งแรง

แล้วปูกระดาน วางบุษบกบนบุษบกจะนำพระพุทธรูปยืนรอบบุษบกก็วางเครื่องดนตรีไว้บรรเลง เวลาเคลื่อนพระ

ไปสู่บริเวณงานพอเช้าวัน 1 ค่ำ เดือน 11 ชาวบ้านจะช่วยกันชักพระ โดยถือเชือกขนาดใหญ่ 2 เส้นที่ผูกไว้กับ

พญานาคทั้ง 2 ตัว เมื่อถึงบริเวณงานจะมีการสมโภช และมีการเล่นกีฬาพื้นเมืองต่างๆ กลางคืนมีงานฉลองอย่าง

มโหฬาร อย่างการชักพระที่ปัตตานีก็จะมีชาวอิสลามร่วมด้วย (ข้อมูลจาก kapook.com)

ในจังหวัดนครศรีธรรมราช ก่อนวันชักพระ 2 วัน จะมีพิธีใส่บาตรหน้าล้อ นอกจากอาหารคาวหวานแล้ว ยังมี

สิ่งที่เป็นสัญลักษณ์ของงาน คือ "ปัด" หรือข้าวต้มผัดน้ำกะทิห่อด้วยใบมะพร้าว บางที่ห่อด้วยใบกะพ้อ

(ปาล์มชนิดหนึ่ง) ในภาคกลางเขาเรียกว่า ข้าวต้มลูกโยน ก่อนจะถึงวันออกพรรษา 1 - 2 สัปดาห์ ทางวัด

จะทำเรือบก คือ เอาท่อนไม้ขนาดใหญ่ 2 ท่อนมาทำเป็นพญานาค 2 ตัว เป็นแม่เรือที่ถูกยึดไว้อย่างแข็งแรง

แล้วปูกระดาน วางบุษบกบนบุษบกจะนำพระพุทธรูปยืนรอบบุษบกก็วางเครื่องดนตรีไว้บรรเลง เวลาเคลื่อนพระ

ไปสู่บริเวณงานพอเช้าวัน 1 ค่ำ เดือน 11 ชาวบ้านจะช่วยกันชักพระ โดยถือเชือกขนาดใหญ่ 2 เส้นที่ผูกไว้กับ

พญานาคทั้ง 2 ตัว เมื่อถึงบริเวณงานจะมีการสมโภช และมีการเล่นกีฬาพื้นเมืองต่างๆ กลางคืนมีงานฉลองอย่าง

มโหฬาร อย่างการชักพระที่ปัตตานีก็จะมีชาวอิสลามร่วมด้วย (ข้อมูลจาก kapook.com)

พิธีชักพระทางน้ำ

พิธีชักพระทางน้ำ

ก่อนถึงวันแรม 1 ค่ำเดือน 11 ทางวัดที่อยู่ริมน้ำ ก็จะเตรียมการต่างๆ โดยการนำเรือมา 2 - 3 ลำ มาปูด้วย

ไม้กระดานเพื่อตั้งบุษบก หรือพนมพระประดับประดาด้วยธงทิว ในบุษบกก็ตั้งพระพุทธรูป ในเรือบางที่ก็มี

เครื่องดนตรีประโคมตลอดทางที่เรือเคลื่อนที่ไปสู่จุดกำหนด คือบริเวณงานท่าน้ำที่เป็นบริเวณงานก็จะมีเรือพระ

หลายๆ วัดมาร่วมงาน ปัจจุบันจะนิยมใช้เรือยนต์จูง แทนการพาย เมื่อชักพระถึงบริเวณงานทั้งหมด ทุกวัดที่มา

ร่วมจะมีการฉลองสมโภชพระ มีการละเล่นต่างๆ อย่างสนุกสนาน เช่น แข่งเรือปาโคลน ซัดข้าวต้ม เป็นต้น

เมื่อฉลองเสร็จ ก็จะชักพระกลับวัด บางทีก็จะแย่งเรือกัน ฝ่ายใดชนะก็ยึดเรือ ฝ่ายใดแพ้ต้องเสียค่าไถ่ให้ฝ่ายชนะ

จึงจะได้เรือคืน (ข้อมูลจาก kapook.com)

ก่อนถึงวันแรม 1 ค่ำเดือน 11 ทางวัดที่อยู่ริมน้ำ ก็จะเตรียมการต่างๆ โดยการนำเรือมา 2 - 3 ลำ มาปูด้วย

ไม้กระดานเพื่อตั้งบุษบก หรือพนมพระประดับประดาด้วยธงทิว ในบุษบกก็ตั้งพระพุทธรูป ในเรือบางที่ก็มี

เครื่องดนตรีประโคมตลอดทางที่เรือเคลื่อนที่ไปสู่จุดกำหนด คือบริเวณงานท่าน้ำที่เป็นบริเวณงานก็จะมีเรือพระ

หลายๆ วัดมาร่วมงาน ปัจจุบันจะนิยมใช้เรือยนต์จูง แทนการพาย เมื่อชักพระถึงบริเวณงานทั้งหมด ทุกวัดที่มา

ร่วมจะมีการฉลองสมโภชพระ มีการละเล่นต่างๆ อย่างสนุกสนาน เช่น แข่งเรือปาโคลน ซัดข้าวต้ม เป็นต้น

เมื่อฉลองเสร็จ ก็จะชักพระกลับวัด บางทีก็จะแย่งเรือกัน ฝ่ายใดชนะก็ยึดเรือ ฝ่ายใดแพ้ต้องเสียค่าไถ่ให้ฝ่ายชนะ

จึงจะได้เรือคืน (ข้อมูลจาก kapook.com)

ประเพณีอีสาน

ประเพณีเทศน์มหาชาติ หลัง วันออกพรรษา นิยมทำกันหลัง วันออกพรรษา พ้นหน้ากฐินไปแล้ว ซึ่งกฐินจะทำกันภายใน

1 เดือนหลังออกพรรษาในภาคอีสานนิยมทำกันในเดือน 4 เรียกว่า "งานบุญพระเวส" "บุญพะเวส" "บุญผะเหวด" แล้วแต่

สำเนียงแต่ละพื้นถิ่น หลังจากบุญข้าวจี่ (เดือนสามบุญข้าวจี่ เดือนสี่บุญพะเวส) ซึ่งเป็นช่วงที่เสร็จจากการทำบุญลานข้าว

(งานเทศน์มหาชาตินั้นจะทำในเดือนไหนก็ได้ไม่จำกัดฤดูกาล)

ฮีดสิบสอง (เป็นส่วนของกุศโลบายสร้างความสามัคคี: ผู้เขียน)

เดือนอ้าย-บุญเข้ากรรม (ปริวาสกรรม)

เดือนยี่-บุญคูณลาน(บุญลานข้าว)

เดือนสาม-บุญข้าวจี่

เดือนสี่-บุญผะเหวด

เดือนห้า-บุญสงกรานต์

เดือนหก-บุญบั้งไฟ

เดือนเจ็ด-บุญซำฮะ(ปัดเป่าเสนียดจัญไร)

เดือนแปด-บุญเข้าพรรษา

เดือนเก้า-บุญข้าวประดับดิน

เดือนสิบ-บุญข้าวสาก

เดือนสิบเอ็ด-บุญออกพรรษา

เดือนสิบสอง-บุญกฐิน

1 เดือนหลังออกพรรษาในภาคอีสานนิยมทำกันในเดือน 4 เรียกว่า "งานบุญพระเวส" "บุญพะเวส" "บุญผะเหวด" แล้วแต่

สำเนียงแต่ละพื้นถิ่น หลังจากบุญข้าวจี่ (เดือนสามบุญข้าวจี่ เดือนสี่บุญพะเวส) ซึ่งเป็นช่วงที่เสร็จจากการทำบุญลานข้าว

(งานเทศน์มหาชาตินั้นจะทำในเดือนไหนก็ได้ไม่จำกัดฤดูกาล)

ฮีดสิบสอง (เป็นส่วนของกุศโลบายสร้างความสามัคคี: ผู้เขียน)

เดือนอ้าย-บุญเข้ากรรม (ปริวาสกรรม)

เดือนยี่-บุญคูณลาน(บุญลานข้าว)

เดือนสาม-บุญข้าวจี่

เดือนสี่-บุญผะเหวด

เดือนห้า-บุญสงกรานต์

เดือนหก-บุญบั้งไฟ

เดือนเจ็ด-บุญซำฮะ(ปัดเป่าเสนียดจัญไร)

เดือนแปด-บุญเข้าพรรษา

เดือนเก้า-บุญข้าวประดับดิน

เดือนสิบ-บุญข้าวสาก

เดือนสิบเอ็ด-บุญออกพรรษา

เดือนสิบสอง-บุญกฐิน